Chapt

er: World

Stimmen aus dem Exil

Das „Stimmen aus dem Exil“- Kollektiv des Thalia Gauß bloggt auf unserer digitalen Bühne. Nach dem Rückblick auf die bisherigen Ausgaben der szenischen Lesereihe, zeigen wir unter dem Titel „Stimmen aus dem Exil – Chapter: World“ neue Texte, Illustrationen, Videos und vieles mehr von weltweiten Stimmen!

How did I get here ?

How did I end up here?

Where did I come from?

Where do I start from ?

Which direction I go?

This road I know not?

This eru, weight, I carry

it suffocates me, it is too much

buy I carry it still

can I throw it away

If I knew about privileges

structural and organization prejudice

If I knew about race, color

boundaries, colonies, passports

would I still be black

Did I know about hunger, poverty, suffering, darkness

did I know about possession of Gold, Diamond, Oil

did I know about the coming of genocide

killing, hating, killing and killing

if I knew that I would become a generation of subject and ridicule

if I knew about owning so much

if I knew those who stole, raped, killed and make kill

if I knew about returning to them with the same channel used to come I

Our sons have heard your tales

Our daughters now know their friends

Our earth vomit the stench of horror

But in your land, you live like kings

Our tongues now speak your language

Exploration is what you do

Commotion is what we get

You have to stay away right now

If don’t, I will lost our mind

We don’t want our prophets killed no more

This place called home, doesn’t feel so any more

In it I feel hot, tremble in distress and endless pain

In it, love has been stabbed to death

Peace now resides with guns

Sisters rape sisters

We get chalk for medicine, and wood for food

Leaders sell lies, even to the younger generation

Not anymore does it rain in season

The prison is now a home for justice

sadly, we flee to the door step of our tormentors

Slavery, religious bigotry, colonialism, genocide, ethnic discrimination, corruption,

mitigation Maladministration, misappropriation, vilification, embezzlement

mismanagement, defraudment Terrorism, Nepotism bombing…

Where did we get such names from?

I know, your names

I know you, all of you

In my palms, I have written your names

in my head it rings one by each

I know, I know your name

Structural slavery

environmental segregation

modernized colonization

I know, I know your name

I smell your disguise

I have carried out the autopsy of the carcass in your hidden crematory

Wer aus schwierigen Verhältnissen stammt, sollte das

Recht kriegen, in schwierigsten Verhältnissen weiterkochen zu

dürfen. So möchte es Onkel Murphy. Wer Ordnung nie

gelernt, gehört in den Himmel.

Wer Schulden besitzt, verdient die gerechte Möglichkeit,

diese auch verdoppeln zu dürfen. Vervierfachen. Bis zur Unendlichkeit

und noch viel weiter. Wer das Kind in sich nicht

töten kann, darf das Pausengeld seiner Kinder in Bukarest

auf Hundekämpfe verwetten. Oder auf Fußball. Auf Nacktschnecken

setzen. Oder auf Streichkäse. Kommt die Freiheit, bleiben wir.

Kommt sie nicht, gehen wir zu ihr.

Jeder sollte mal an einer Minderheit geleckt

haben. Bevor Sterne nicht als Bürgen angesehen, ändert sich hier nichts.

Wer kurz davor die Augenfarbe seiner Mutter zu vergessen, dem

soll Gott das Meer zeigen. Wer keine Zähne mehr im Mund hat, braucht gute

Geschichten. Zigaretten sollten einzeln verkauft werden.

Mahnbriefe und Nachzahlungen sollte man bekommen auf rosa Papier.

Jede Seele verdient Streicheleinheiten.

Der Mensch darf sich totsaufen, wenn er nicht mitspielen möchte.

So möchte es Onkel Murphy.

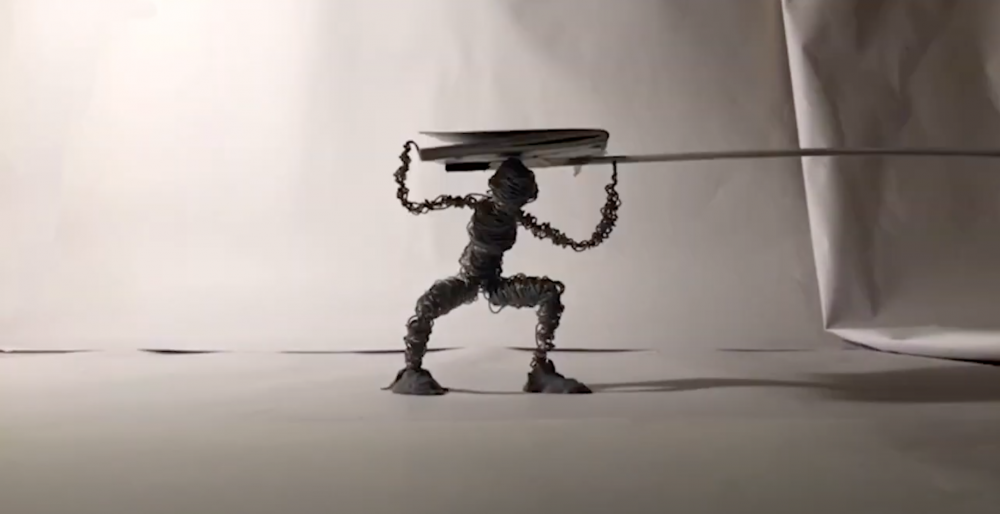

Those trees I cannot grow

and mechanical hospital beds

ache my shoulder blades. Attacked

by man's exponential growth and I am so small

my bedsheets cannot fight back. Attacked

by ink on paper: you will never write like this. Attacked

by every soundbyte;

this muse was not born to be heard. Attacked

and I lack skin; her steel spoon was destined

for homemade chicken broth - not inner thighs.

My armour was performative and my stage

has fallen flat. Attacked

and I have not been mothered. Attacked

and my veins are made of naked wire

hanging between the streetlights of downtown Beirut. Attacked

and I internalize the hollow of the air. Attacked

by the silence in between their words

and the way the tall German's head leans to the side

when I avoid eye contact. Attacked

by a 14-year-old who had just discovered sex

and has yet to make peace with her womb. Attacked

and social distancing makes it hard

to summon an army of wine

and drugs to turn my head the other way -

where there is no battle and every day

is another chance.

Who am I to say to you

what I say to you?

when I’m not a stone burnished by water

to become a face

or a reed punctured by wind

to become a flute..

I’m a dice player

I win some and lose some

just like you or a little less . . .

“Put yourself in our shoes! We are not safe in Moria. We didn’t escape from our homelands to stay

hidden and trapped. We didn’t pass the borders and played with our lives to live in fear and

danger.

Put yourself in our shoes! Can you live in a place that you cannot walk alone even when you just

want to go the toilette? Can you live in a place, where there are hundreds of unaccompanied

minors that no one can stop attempting suicides? That no one stops them from drinking.

No one can go out after 9:00 pm because the thieves will steal anything you have and if you don’t

give them what they want, they will hurt you. We should go to the police? We went a lot and they

just tell that we should find the thief by ourselves. They say: ‘We cannot do anything for you.’ In a

camp of 14.000 refugees you won’t see anyone to protect us anywhere even at midnight. Two

days ago there was a big fight, but until it finished no one came for help. Many tents burned. When

the people went to complain, no one cared and even the police told us: ‘This is your own problem’.

In this situation the first thing that comes to my mind to tell you is, we didn‘t come here to Europe

for money, and not for becoming a European citizen. It was just to breathe a day in peace.

Instead, hundreds of minors here became addicted, but no one cares.

Five human beings burned, but no one cares.

Thousands of children didn’t undergo vaccination, but no one cares.

I am writing to you to share and I am hoping for change…”

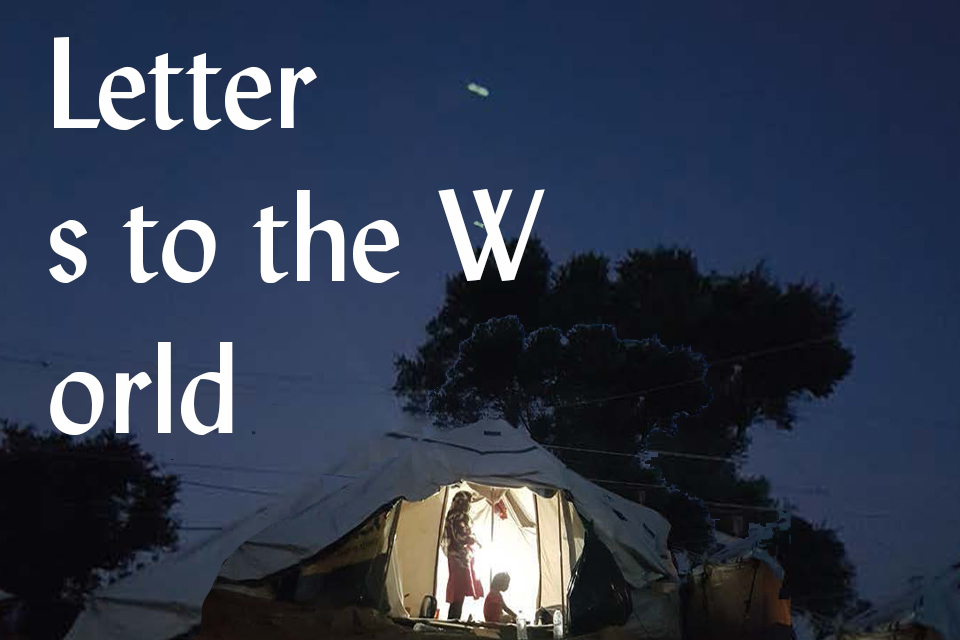

Letters to the World from Moria. Written by Parwana Amiri based on stories told by Temporary

Citizen of Moria Camp on the island of Lesvos in Greece.

Copyright:

Letters: Parwana Amiri 2019 - 2020

Photos : Parwana Amiri, Ahmad Ebrahimi, Judith Buethe, Salinia Stroux, Marily Stroux, Hinrich

Schultze. 2019 - 2020

Supported from w2eu - Watch The Med Alarm Phone

Read the whole Letters: lesvos.w2eu.net / infomobile.w2eu.net

Exhibition from 8 th until 26 th of June at Stadtteilkulturzentrum Kölibri, Hein-Köllisch-Platz 12

I am Parwana Amiri,

I was born in Herat province in Afghanistan. I have four sisters and two brothers and

I am the fifth eldest child in my family. We had to flee due to the political problems

my father had. One and half years ago we became refugees. After crossing the

borders through Pakistan, Iran and Turkey we arrived on Lesvos Island in Greece.

We reached Moria refugee camp on 18. September 2019.

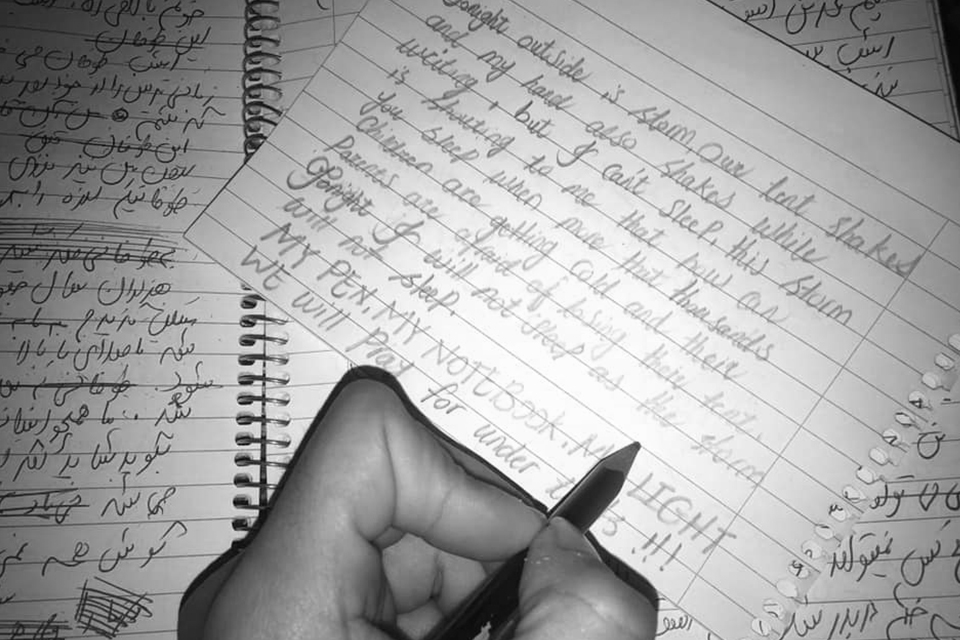

When we arrived in Moria and I saw everybody’s daily problems, I couldn’t sit aside

and not do anything. I have a deep belief in words and their effects. I knew that

using words to show the reality is the only way to make change.

After becoming active in the camp and starting to build trusting relationships with

people, I began writing articles about our living conditions – my story and theirs.

Stories that had never been heard or read in the media. Stories that never got out of

this overcrowded camp.

You can lose yourself at any point in time in your life, but you must stay strong when

others need you. This is what I could do for myself and others with my own

resources. I stayed strong because I was doing something that made sense in this

senseless jungle. I was motivated to hold my pen and keep writing for us all in Moria

– for we all need to continue the struggle.

During this short time, under these terrible conditions that no human deserves, I did

a lot. I worked with “Waves of Hope for Future”, which is a self-organized school and

I participated in the “Refocus Media Lab”.

Raus das: (I taught different classes, I coordinated an art exhibition, I wrote a book

about being a volunteer teacher, I participated in journalism workshops and I wrote

film scripts.)

I could find my way with solidarity people.

I wish for peace in the world. I wish for a world without borders. I want a world where

children don’t die from malnutrition and women don’t die from violence. I wish to live

in an equal world. I wish for a world where no one is poor and no one is rich. Our

dreams will become reality only if we communicate and I want to be one connector

bringing people together and even continents. I wish for peace and safety for all

people.

I wish strong hearts for all those that are forced to escape their homes, to not lose

their path when facing hardships. The hardest stones are formed in the high heat of

volcanoes.

I didn’t know that in Europe people get divided in the ones with passports and the

ones without. I didn’t know that I would be treated as ‘a refugee’, a person without

papers, without rights. I thought we escaped from emergencies, but here our arrival is

considered an emergency for the locals. I thought our situation in the camp is an

emergency, but in Europe the meaning of emergency for people like ‘us’ is to be

dead.

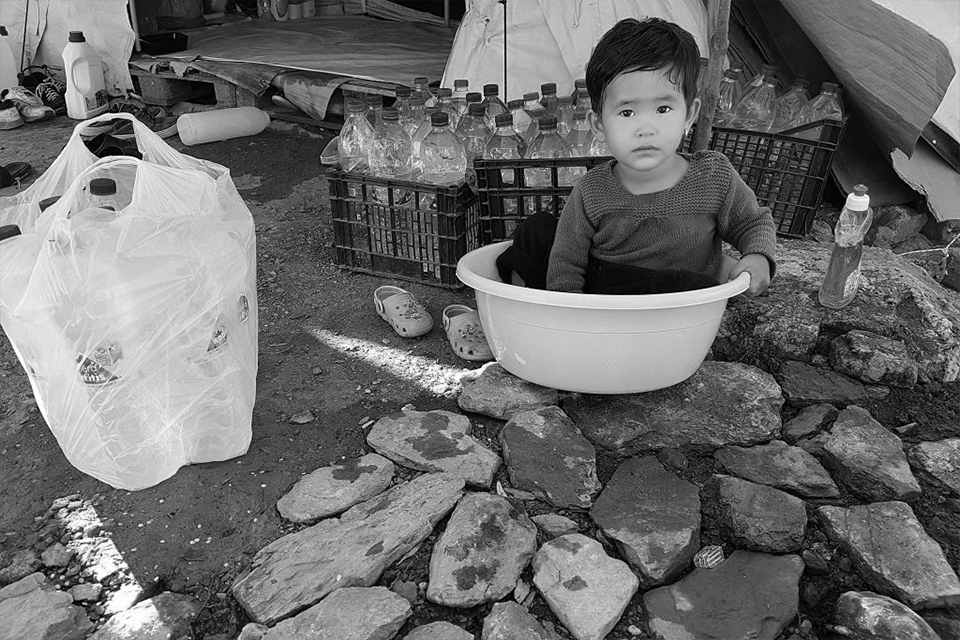

Under the conditions we live exposed to heat in summer and rainfalls in winter, in the

middle of garbage, dirt and sewage water, unsafe in permanent stress and fear facing

the violence of the European Asylum System in this small world of 15,000 people –

we are all emergency cases.

In fact in Moria, most arrived already with injuries in their souls and sometimes on

their bodies. But here everyone gets ill, also the healthy, and our situation let our

sicknesses turn to emergencies very fast.

Consider the story behind life in Moria hotspot: Having spent days, weeks or months

walking up and down hills, over rocks and in between trees while living in a forest.

Standing in queues for hours. Lost between what we think of as protection and what

they create to hinder us reaching it.

In Europe we become like ping pong balls. The authorities shoot us from one office to

another, back and forth without ending and without understanding what, where, why –

which makes our situation worse and worse. Even the ‘success story’ of receiving

finally a residence permit can’t end the discriminating looks we have to live with every

day.We are not another quality of people; another class of humans; another kind. We are

different people with thousand different stories. What unites us is just that we had to

leave our homes.

So stop treating us different. Stop lying and pretending that people are safe here.

Stop saying Europe was a better place, when it is only better for some and not even

accessible for others.

We are not treated like being a part of Lesvos’ population, like Greeks, like

Europeans. Our destiny depends on a bureaucrats decision, on the economical value

of a political decision in favour of migration or not, on the political mood dominant in

the continent, on European strategies and plans. It is not build on the foundation of

‘us’ and ‘you’ being one kind.

I am a girl in a tent and I am thinking about this world as the days won’t pass by and I

am waiting for the permit to leave this place.

My pen won’t brake unless we won’t end this story of inequality and

discrimination among human kind. My words will always break the borders you

built.

Parwana Amiri

I am mother of three children and wife of a sick husband. He has a hernia on his

backbone. He cannot walk. Neither should he get tired. So, I must look after my entire

family on my own.

I am a woman, softer than flowers, but this life makes me harder than rocks.

Every day, as the sun rises, my mission starts. I wake up at 5am. I spread the blanket

over my children. Then I go to get food. I walk 800 meters to the food line. The line

starts at 6:30am., but I want to be up front, the first one among a thousand women.

All this waiting for just 5 cakes and one litter of milk, which I suspect is mixed with

water.

My boy has a kidney infection for five years now. He cannot tolerate hunger. I must

go back as fast as I can.

When back, I gather all the blankets and spread them on the tent’s floor.

I sweep in front of my tent. With my own hands I made a broom from tree branches. I

wet the soil with water to prevent the dust and dirt from coming inside.

I hardly finish and, once again, I must run to the food line for taking lunch. The queue

starts at 11:30am although they distribute the food only at 13:00pm. So the whole

waiting process, under unbearable conditions, starts for me again. In the line for

hours, I do not know what happens to my children: Are they well? Are they safe? Has

my son’s pain started?

We have been here for 200 days. And every week, we eat the same food – repetitive,

tasteless, with no spices, little salt and oil. Three times a week beans, once meatballs, once chicken and once rice with sausage, which we don’t know for sure if it is Hallal. But I force my children to eat so they won’t stay hungry.

Securing meals is only one of my tasks. I must also wash my family’s clothes. As my

children are all the day outside, their clothes get really dirty. Trying to clean the stains

my hands get all chapped, the skin cracks. I need to rub them with oil every night.

I hang the clothes and, tiredly, I walk, once more, to the line for dinner—dinner only

by name. Dry bread, one tomato and one egg. We must wet the bread to chew it.

This is no dinner. When we have nothing to eat, we have to eat onion with bread (it’ s

hot for children but we try to eat it cheerfully).

When my day finishes, I am really exhausted. But I do not want my family to notice. I

fix my face. It should show no sadness, no fatigue. I hide my chapped hands from my

husband and my children.

Sometimes, I don’t make it to the food line, because of the long queues, which I have

to stand in to visit the clinic. I go there at 7:00am, but the process is very slow and,

usually, every patient takes about 20 minutes inside. Then, the situation of my child

gets worse than it normally is, because of his exposure to the sun and the polluted air

outside. We need a specific permit to go get some drinking water.

Waiting in queue for four hours, without any toy or game, is very hard for children. It is

equally hard for pregnant women like me. I know my husband is not happy when he

sees me trying to manage on my own every day. But there is no other way. We don’t

have anyone to help. Only ourselves. And he cannot.

I am my family’s strength, their courage, their hope. If I lose hope, who will stand by

them? Who will help them? No one.

When the sun sets and darkness spreads, I am filled with fear. I fear also when it

becomes cloudy and it rains. I fear the wind, I fear the cold. How will I protect my

family? With what will I protect them, when we do not have anything?

When you don’ t have any resources, what are you going to do? I collect the blankets

from the floor and spread the cardboards instead. The blankets are our covers at

night and the carpets during the day.

I am a mother and wife. My children are the pieces of my heart and my husband is my

blood. They are all I have in my life. But who am I for myself?

I don’t have time to even see myself in the mirror. I don’t have time to comb my hair

once a day. I don’t have time to brush my teeth in 24 hours. I can’t take care of my

skin. I can’t be a woman.

I am content to sacrifice myself to make a comfortable life for my children and my

love, my husband. Because I am a woman. It is my choice to be like this. Life is hard

here and there is nowhere good to go.

I was given the documents to go to the mainland. But I canceled my ticket. On the

mainland, the authorities will put us in a hotel, far from hospitals or clinics that we

depend on. What am I going to do there with my sick child and my husband and

myself pregnant? We need (specialised) doctors. We need protection and care.

I am sorry that I don’ t have time to speak with my family as a mother, as a wife and

as a friend. Because I don’ t have more power. I can’ t do more in 24 hours, than

bring food, go to clinics, stand in lines.

I have had enough. I can’t continue anymore. Truly, if I didn’t have my children, I

would have committed suicide. I live only because it is worth living for them. And now,

I am pregnant and I carry one more life in me.

I am one for myself, but four for my family. Soon I will be five…

Perwana Amiri

p.s. For all the mothers!

Life has normally ups and downs, but my life has always been flat. I have

been trapped in a deep valley.

I am getting close to my lives’ end. At an age when every old woman needs

to rest, I push my heart to work and earn money for my husband who

suffers from heart problems and for our son.

Yet, instead of taking care of my husband’s sickness, we must first prove

his illness, they say. Our words don’t count, but only papers. Do we need to

take out his heart to show he is ill?

After many medical tests we undertook with many difficulties, they told us

that his illness should be certified by the doctors of the big hospital. The

name of his sickness has to be written in words on a paper. They didn’t tell

us, who will cover his transportation costs to go to town? Of course no one

will!

When my husbands’ heart suffered, I desired my death as I could not

help without a Cent in my pocket…

Days passed. I decided to build a tandoor (trad. oven) to bake break and

sell it. I thought, I could purchase the necessary ingredients by borrowing

some money from one of our relatives, who had a cash card. Just 0,50

euros, that’s all I needed! I touched the fifty cents and my old hands were

shaking. Not only because of my old age. Not only because of my worry for

my sick husband. They shake at the thought of the thousand year old olive

tree that will burn under my tandoor. I tremble with the idea of the axe

reaching the old tree. I can feel its crying out. Yet, I must have fire to bake

my bread. …

But it is the rule of nature: Eat or be eaten.

How many troubles have I faced in hope of today’s bread to cure my

husband. Yet, I need a cure too. My heart burns at the thought of the felled

burning trees. But, I must ignore my heart, I must take care of my old

husband. I must bake the bread!

With my old hands I shall prepare dough that needs powerful arms, but my

arms are weak and shaking. I will do it! I will wake up at 4:00am! First, I will

read my prayers. Then I will start the dough. Flour, oil, salt, yeast and

water. I will mix them all together. And then. I will let the dough rest. Once

raised, I will cut out small shapes and let them rest again. By 7:00am the

pieces will be ready for the tandoor.

My son walks far away onto the hills to collect dry wood and start the fire.

Oh, how the old trees turn into ashes. My son instead of going to school will

go around trying to sell the bread when its ready. From the early morning

until the late evening he will call people to buy it. There are a lot of bakeries

nowadays in Moria and selling is very difficult.

Hundreds of steps, hundreds of moves, a lot

of sweat in respect of life, in respect of the

bread and in respect of the trees.

This is our situation and this is how we spend our days. No one knows

about it. No one can see. I have always been in the flat valley. No ups in my life. My voice, my cries will never be heard. They are old and weak. My shaking hands will be never held by a stronger hand. In this age, they still

have to hold my family.

I want to be a friend of nature, not its enemy. I want to pass my last days

with my family in rest, to have some comfort, to sit for days in the shadow

of the trees, not to burn them. But life is very ruthless. Sometimes we

people are obliged to do things we don’t want to do it. See what life forces

us to do…

What if someone in this world would hold my

hands, so I could become an ally of nature

walking away from the deep valleys, up to the

mountains and the sun?

Perwana Amiri

I am young girl full of energy, power and self-confidence. Everyday there

are a lot of voices inside me inviting me to let this energy out. BUT I am in

Moria, between thousands of unclean eyes, that are looking to my body

and not to my soul. These eyes bother me. I can not play volleyball. I can

not even just walk straight down one path. My head should be down. When

I am crossing the roads it is difficult like passing the borders for me.

200 metres to the toilets. 400 metres to the food queue. Again 400 metres

back. Along this distance there are hundreds of eyes looking to me.

Girl-molesting is common, is daily. Even when they disturb us we are not

supposed to answer them. We are not supposed to turn around. We can

not say: ‘Don’t follow me! Stop bothering me!’

While washing my clothes I feel ashame, because boys are looking to me. I

can’t look back to them, because they will misunderstand. So all sport

places are used only by boys, all playgrounds are used only by boys. And

we are locked inside.

Even men in the age of my father look to my body. I don’t know where I

am. This doesn’t look like Europe here. When I was at school I learned that

Europe is the mother of freedom, but I am living in the middle of eye

violence. There are everywhere eyes. There is nowhere freedom. I am a

prisoner here and this is the jail. I will not be able to forget these memories.

Instead of playing with other girls, I have to stay inside. Instead of walking

proudly, I should walk with my eyes turned down. I am forced to feel shame

and fear.

See, I am actually like you. I am thirteen years old. I am a young girl. But I

have to wear a scarf because the look of my hair is a source of their lust,

they say. Why I should cover my head, because they cannot control

themselves? Why I should cover my head at all? Why I have to get limited,

punished? I am a human being but they are looking to me like animals, like

I was their prey. I am afraid of these wolves. I am afraid of losing my

honour, the respect and I start feeling bad just because of my gender.

But it’s enough! Stand up girls! Stand up women! We are not their objects

of lust! We are not the prey of wolves! We should shout out that we want to

be safe! We want our rights! We want to look up!

Perwana Amiri

P.S. I am sorry for all of Moria‘s girls who suffer the same, and specially for

my sisters.

Wouldn’t you shout, to the world, your total disbelief?

What would you say to the world if, instead of who you are now, you were

one of those 20,000 thousand homeless refugees in the camp of Moria,

that the winter turns into a hell and the summer into the Sahara desert?

Wouldn’t you shout, to the world, your total disbelief?

And what would you say if, after days of walking through mountains,

forests, plains, deserts and between valleys, without food and water, in cold

weather, without blankets and warm clothes, yet full of hope about your

reaching Europe, you found yourself, instead, behind Moria’s jail door, with

your dreams of sleep-ing in a warm and safe place shattered?

Wouldn’t you shout, to the world, your total disbelief?

And what would you say, if, awake at night, feeling cold and afraid, you

heard the crying of your very sick child and realised how little you could do

to save it – begging for 2 euros to buy a bus ticket to the hospital and,

when then, having to wait endless hours for someone to take care of your

dying baby?

Wouldn’t you shout, to the world, your total disbelief?

And what would you say if, in the winter, you had to endure, with no real

shel-ter, the cold, the rain, the open running sewage, the piles of rubbish,

praying for the sun that seemed never to rise? What would you say, if your

shoes sank in the mud and you had to pick them up with freezing hands?

Wouldn’t you shout, to the world, your total disbelief?

And what would you say if, in spite of your fear of rape, harassment,

theives, you had to go out of your tent, for your daily, natural needs?

Wouldn’t you shout, to the world, your total disbelief?

And what would you say if, homeless, without a husband, having lost your

son in the waves, your hair white and your body weak, you had to queue, in

rainy and stormy weather, together with 5000 more women, for a mouthful

of food?

Wouldn’t you shout, to the world, your total disbelief?

And what would you say, if you worshiped the sun, pleading that he comes

out just for a bit to warm your children’s bed and their freezing feet, in the

cold of winter?

Wouldn’t you shout, to the world, your total disbelief?

And what would you do, if you saw girls selling their bodies for money?

Wouldn’t you spit on the world? And what would you say, if you had to live

in this jail of Moria for more than one year, your only “crime” being your

search for safety and for that precious blue stamp that recognises you as a

refugee and makes your dream come true.

Wouldn’t you shout, to the world, your total disbelief?

And what would you say, if simple things like heating and electricity

(necessary to charge your mobile phone and speak five minutes with your family, who want to learn whether you are alive or lost in the waves of the sea), a warm blanket, a shelter, a mouthful of warm food and a cup of tea

become an impossi-ble wish to be had only in your dreams?

After becoming active in the camp and starting to build trusting

relationships with people, I began writing articles about our living conditions

– my story and theirs. Stories that had never been heard or read in the

media. Stories that never got out of this overcrowded camp.

You can lose yourself at any point in time in your life, but you must stay

strong when others need you. This is what I could do for myself and others

with my own resources. I stayed strong because I was doing something

that made sense in this senseless jungle. I was motivated to hold my pen

and keep writing for us all in Moria – for we all need to continue the

struggle.

During this short time, under these terrible conditions that no human

deserves, I did a lot. I worked with “Waves of Hope for Future”, which is a

self-organized school and I participated in the “Refocus Media Lab”.

I could find my way with solidarity people.

I wish for peace in the world. I wish for a world without borders. I want a

world where children don’t die from malnutrition and women don’t die from

violence. I wish to live in an equal world. I wish for a world where no one is

poor and no one is rich. Our dreams will become reality only if we

communicate and I want to be one connector bringing people together and

even continents. I wish for peace and safety for all people.

I wish strong hearts for all those that are forced to escape their homes, to

not lose their path when facing hardships. The hardest stones are formed

in the high heat of volcanoes.

Parwana Amiri

Black

In Europe, I've had

a lot more hummus

than back home. I've been on more

demonstrations, popped more

beers, danced more hours

in the name of

solidarity. I have also

known of more Floyds

remembered

only for their deaths.

The justice masquerade dances

two steps to the left, three

to the right.

We discuss recipes but not borders;

flatbread but not arms.

Accessories: scribbling

I CAN'T BREATHE

on Amazon Prime boxes.

Refugees Welcome merchandise

sells well on the Reeperbahn.

I'm sorry

you cannot

undo history

in your kitchen.

Shorouk El Hariry

“Africa Prophet”

By Ekow Quagraine

Come let’s lift our eyes to the hills, cometh our health and give us health.

And strength rastafari in these challenging times.

Never let my foot be moved, on the back of the battlefields I can't lose.

And let the words of my mouth and the meditation be true.

Africa awaits its creator those at home and abroad.

Africa awaits its creator those at home and abroad.

So let peace be within the walls and prosperity in the palace, to every rebel with a course.

Jah is watching over his prophet.

Organize and centralize and come as one.

Leave no one behind but you singled me out, is it because I am different? Or because I am a threat to you? No one can show a child who is god. You did it to my father and you did it to my mother. When I questioned you, you told me two wrongs don't make a right, but you repeat your wrongs everyday.

Killing me will not make me fear you, but only make me stronger and more furious. You can't practice the peace you preach. Remember you said before peace there must be war. Before you build you cause a lot of destruction. Sorry, but you have to accept this: I am here and I will always be here. You can't tell me to forget but I can forgive. My son is your grandson, and will be the root of your kind, but don't ask why when the tables turn. Killing me will not make me fear you but only make me stronger and more furious.

BLACK LIVES MATTER #gegenrassismus #noracism #لاللعنصرية

Die aktuelle Debatte über Asylsuchende findet auf dem Rücken der Geflüchteten statt. Nicht die Anzahl ist alarmierend, sondern der gesellschaftliche und institutionelle Umgang mit jenen, die ihre Heimat, wegen Krieg, Verfolgung und Armut verlassen mussten. Abgesehen davon, dass Flüchtlingslager in Griechenland maßlos überfüllt und überfordert sind, müssen Zelte, Decken und Schlafsäcke von den Neuankömmlingen käuflich erworben werden. Obdach gibt es also nur gegen Bezahlung. Solche Lager und andere offizielle Stellen werden von den Betroffenen daher gemieden, um nicht nur einer Registrierung in Griechenland zu entgehen, denn die meisten Asylsuchenden kennen die Dublin-Verordnung, die sonst einen späteren Asylantrag bspw. in Deutschland unzulässig macht. So machen sie sich verlassene Züge, Häuser und Fabrikanlagen zu Eigen und hausen unter menschenunwürdigen Bedingungen.

Vor allem junge Männer machen sich auf den gefährlichen und weiten Weg über die Balkanroute. So überqueren bis zu 700 Menschen am Tag den griechisch-türkischen Grenzfluss Evros, um über Thessaloniki noch tiefer nach Europa zu gelangen. Entweder zu Fuß, als blinder Passagier auf Frachtschiffen und Güterzügen oder wie die wenigsten mit Hilfe von teuren Schmugglern.

Während die Augen Europas auf das Mittelmeer gerichtet sind, greifen maskierte Grenzsoldaten entlang der Balkanroute zu harten Mitteln. Es wird von unermesslicher Brutalität, Misshandlungen bis hin zu Raub und Freiheitsberaubung berichtet. Eingeschüchtert und gedemütigt soll es ihnen eine Lehre sein. Diese sog. Pushbacks werden von den Offiziellen geduldet, verstoßen massiv gegen das Völkerrecht und verletzen sowohl die Grundrechte-Charta der EU als auch die Genfer Konvention. Laut Dokumenten des türkischen Innenministeriums wurden so im letzten Jahr etwa 60.000 Menschen allein aus Griechenland illegal abgeschoben.

Eine Reportage von O-Young Kwon.

Fotos und Texte von O-Young Kwon

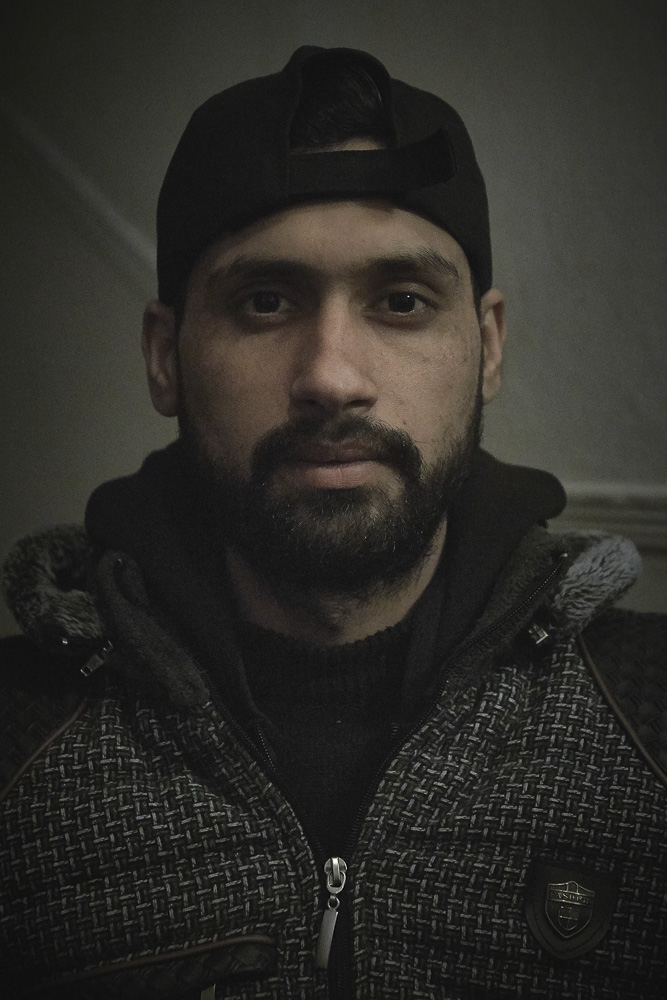

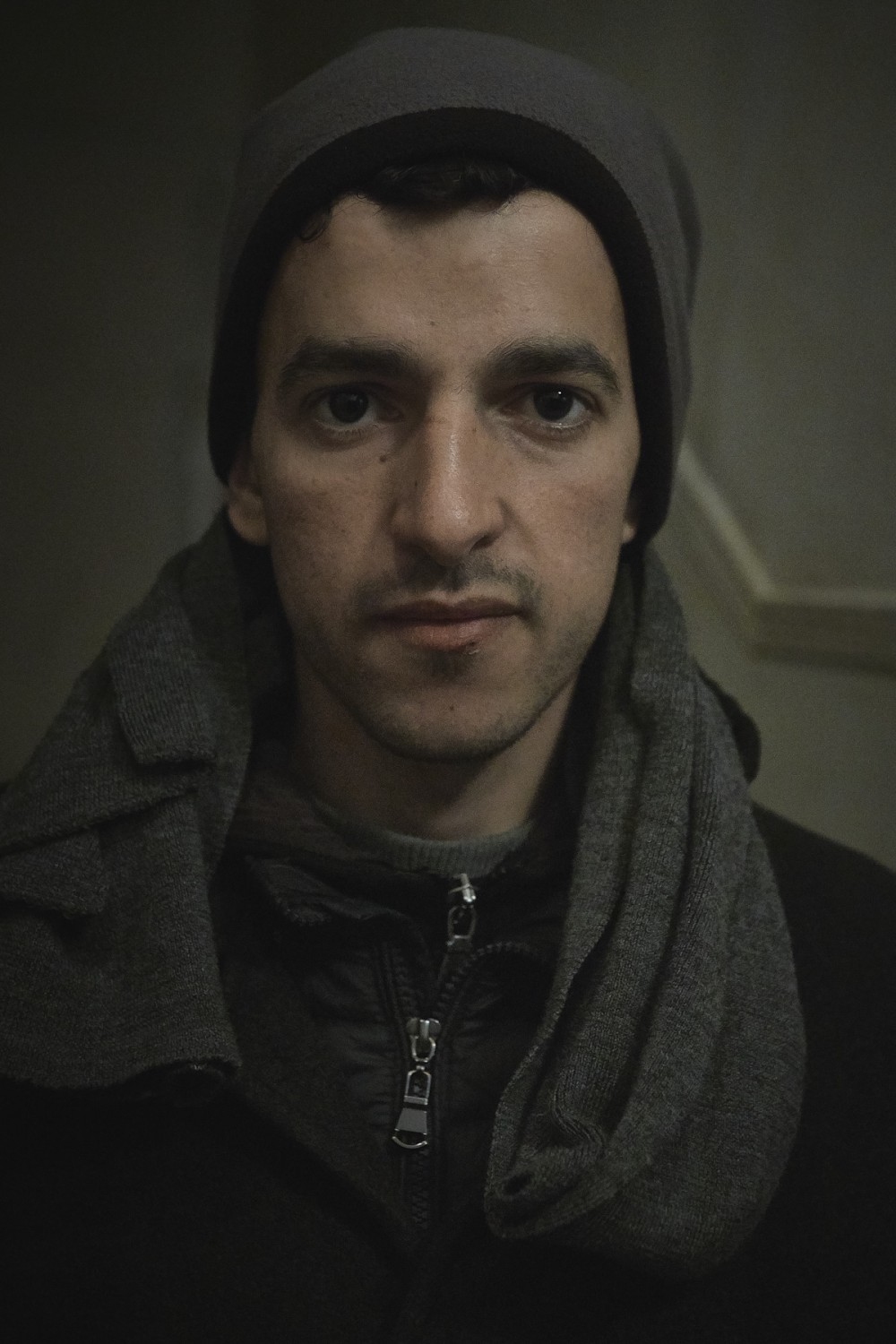

Hassan, 26, Marokko

[Obwohl] ich neben meinem Studium gleichzeitig arbeitete, mußte ich [Marokko], aufgrund von Armut [und Korruption], verlassen. […] Ich möchte meiner Familie, meiner Mutter, helfen. […] Ich habe es dreimal versucht, beim vierten Mal konnte ich [den Evros überwinden]. […] Ich möchte doch nur Arbeit und eine Familie haben und in Frieden leben. […] Wir sind alle Menschen, wir alle denken und haben die gleichen Gefühle.

Abdul, 24, Afghanistan

Von Afghanistan nach Iran [und] von Iran nach Türkei [dauerte es jeweils] drei Wochen und dann noch zwei Wochen von Türkei nach Griechenland, bis nach Thessaloniki. […] Ich habe Familie, aber seit [meiner Flucht] hab ich nichts mehr Kontakt. […] Ein [großen] Bruder hab ich […] und Papa und Mama und dann zwei Schwester klein von mir.

[… Zu Hause] gibt’s viele Gruppe von Terroristen. […] Da siehst du nur Kämpfe, [...] die Leute sterben. […] Die Frau von meine Bruder […], mein Onkel, [dessen Sohn … und] mein Großvater [wurden von der Taliban] erschossen. [… Mein Bruder] ist vor mir geflüchtet, keine Ahnung wo der jetzt ist. […] Wir haben nicht so viel Geld gehabt, deswegen […] bin dann nachher gekommen.

Dass ich Leuten helfen kann, das ist mein Traum! Wenn ich kein Job als Mechatroniker bekomme, dann kann ich malen oder putzen sowas. […] Oder auf dem Bau arbeiten, das kann ich auch.

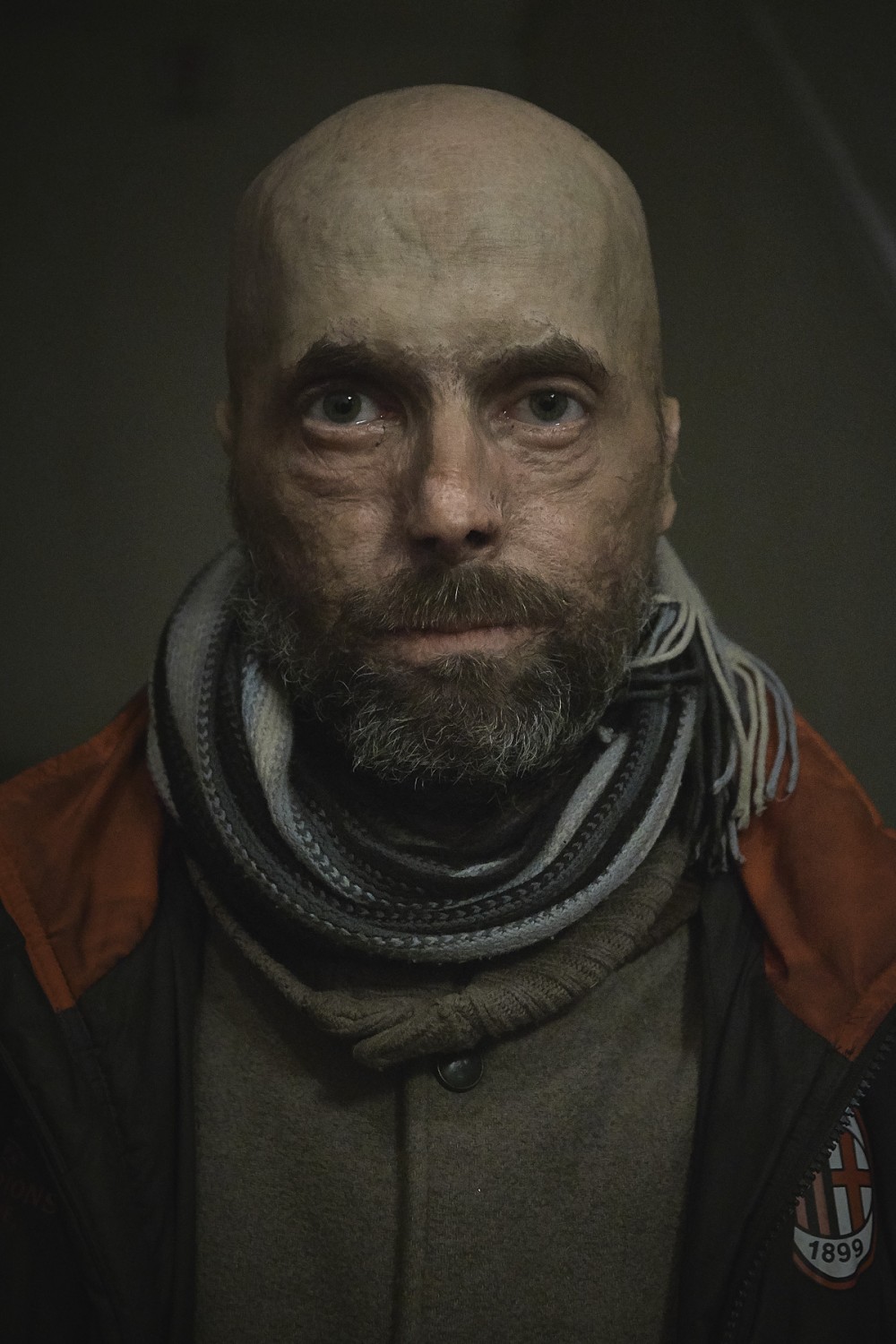

Mahmoud, 40, Syrien

In Syrien vor fünf Jahren ist eine Bombe neben mir gelandet und ich wurde danach in die Türkei für die medizinische Behandlung transportiert. […] Mein Vater und meine Mutter sind dadurch gestorben [und] ich lag acht Monate im Koma. […] Meine Frau [und Kinder] sind noch in Syrien. […] Ich hatte kein Geld, um sie mitzunehmen.

Ich schlafe hier auf der Straße neben dem Bahnhof, da wo der kaputte Zug ist. Ich habe auch keine Kleidung. Seit einem Monat möchte ich duschen und meine Klamotten wechseln.

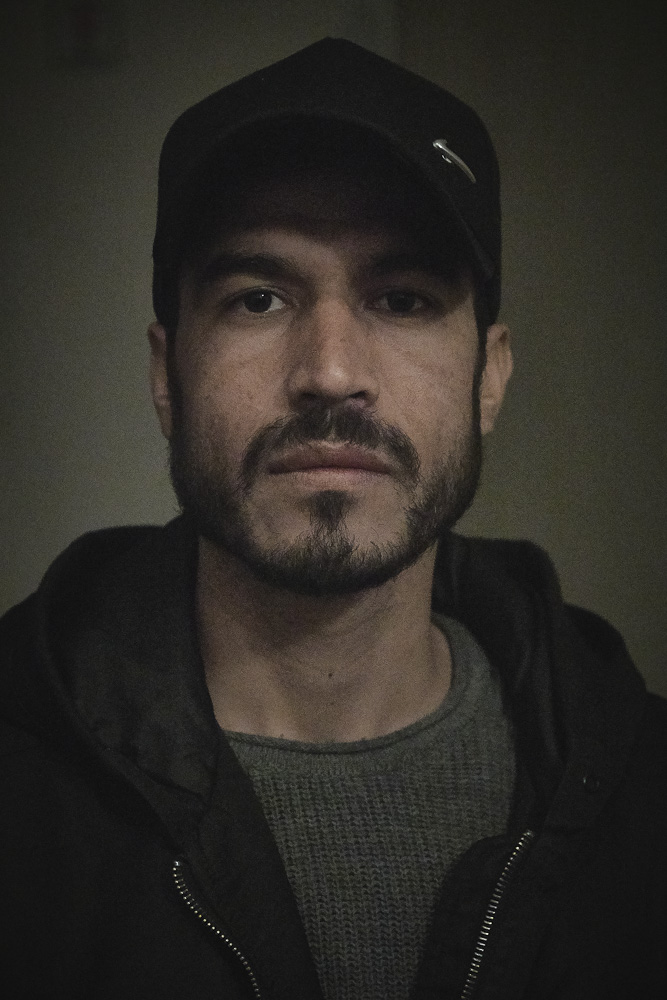

Sabur, 23, Afghanistan

[2011] bin ich nach Österreich gekommen [und] durfte nur […] warten und warten und warten. […] Verschiedene Deutschkurs habe ich selber bezahlt. […] Als ich 2019 meine Interview [zum Asylverfahren] bekommen habe, das war Negativbescheid [...] und Österreich hat mich zurückgeschickt nach Afghanistan. […] Die haben gesagt: „Afghanistan ist jetzt sicher, hier kannst du […] leben.“

„In meinem Dorf gibt’s [...] islamistische Gruppe und du mußt eine Gruppe für dich entscheiden. Zum Beispiel eine gibt’s was die Leute im Dorf leben, die kämpfen gegen Taliban. […] Zweite Gruppe, ist von Taliban. Dritte Gruppe ist [das afghanische] Militär. In jedem Fall: Du mußt kämpfen! Und ich wollte auf gar keinen Fall kämpfen. Ich bin ein Mensch! Wieso soll ich gegen Menschen kämpfen? [...] Ich will nicht Schuld haben an eine andere Tod.“

„Drei Monate war ich in Afghanistan und jetzt bin ich zurück [in Europa...] Ich vermisse meine Familie sehr. […] Mein Traum ist, dass ich glücklich mit mein Familie lebe [und] dass in mein Land [der] Krieg fertig ist. Das ist mein größter Traum.

Fakheur, 23, Algerien

Ich bin der Älteste in meiner Familie. Die Verantwortung liegt allein auf meinen Schultern. […] Meine Mutter ist sehr krank und mein Vater ist verstorben. […]

Ich benötige 5000 Euro [für] die Operation meiner Mutter. […] Also muss ich in ein anderes Land gehen um Geld zu verdienen. […] Ich möchte in Europa studieren, damit ich einen Job kriege.

Ich muß mich opfern. Ich weiß nicht warum mich manche Menschen in Europa nicht mögen, […] obwohl ich doch auch ein Mensch bin wie sie. Ich respektiere sie, also sollten sie mich genauso respektieren.

Haris, 20, Pakistan

Ich brach mein Studium [in Informatik] ab, weil es zu teuer war. Ich habe es für meine Familie getan, […] um Geld für sie zu verdienen. […] Und wir haben […] Probleme mit der Taliban. Bombenanschläge sind dort normal heutzutage.

Zu Fuß über die Grenze in den Iran. Wenn das iranische Militär einen Flüchtling erwischt, wird er zusammen geschlagen [… und] ins Gefängnis gesteckt. Fünf Tage, sechs Tage. […] Die behandeln uns wie Tiere, alle Flüchtlinge. [… Auf dem Weg] vom Iran in die Türkei das Gleiche.

In der Türkei arbeite ich [ein oder zwei Jahre] in einer Fabrik. 12-14 Stunden am Tag.

[Nachdem ich fünfmal gescheitert war nach Griechenland zu kommen], spreche ich mit einem [Schlepper…] und ein Container mit 67 Personen drin kam zu ihm nach Hause. Ich habe ihm dafür 2200 Euro bezahlt. […] Mit einem Jahr Arbeit, habe ich nicht [so viel] verdient. Ich rief meinen Dad an damit er Kredit bei einem Freund oder sonst wem aufnehmen kann, ca. 600 EUR.

#LeaveNo

OneBehind

Hier geht es zu der Petition #LeaveNoOneBehind